OK: I'm past the halfway mark in volume in translating the script. Two things:

- I took a chunk of time to address a long-outstanding issue and replace some lost material. I've mentioned previously that early in the project, without my awareness (or that of other team members), there was a well-meaning attempt to lighten my workload by using AI to translate material and edit some stuff to get it within character limits. The results weren't usable, and I asked that this attempt be discontinued once I found out about it (and for the script to be entrusted to me solely). The problem was that the files with the original, unaltered translations were no longer extant after this editing; I had to retranslate these files, which accounted for about a dozen out of the 80-odd files in the overall script. (I've since kept local copies of what I've translated, so this issue won't arise again.)

- The tech side found an improved script extraction process that's yielded a more-complete, better-formatted set of script files. I do, however, have to move the script from the old files to the new files, do a bit of reformatting, and translate the newfound lines, which should take two to three weeks. (This is my fault for not using the new files earlier; I underestimated the extent of the improvements the new files would bring.)

So there's a bit of health work underway, but it'll end with a more-complete script that, as was always my intention from the very start of the project, is completely human-translated. There's more and surer progress on more fronts, and video files are getting subtitled. Again, this is not the rate of progress I wanted, and I apologize for being indisposed for an extended period, but we're making strides into new territory now, on surer footing.

2025 was not a great year for me. Highlights included the loss of a relationship with a close family member after helping them through a protracted illness, a home break-in, and someone trying to throw me down a flight of stairs. Thankfully, games were there to remind me there are better worlds than this. All three of the titles below are my games of the year, in different ways.

Note: I'm going to be updating this throughout the day and possibly beyond. I'll remove this message once this entry is complete.

MY GAME OF THE YEAR (QUALITY): I remember while playing this pausing to think, with awe, how video games had evolved from largely Alex-in-Lunar-esque power fantasies to a medium that could offer something like Lorelei and the Laser Eyes, telling the tale of a thriller-horror-love/hate story through the aesthetics of German expressionism and the medium of number puzzles. Contrary to what supergreatfriend said in his own praise, I would argue that yes, it is doing a killer7, that level of complexity and symbolic sublimation in its storytelling, just with a personal relationship instead of political drama. It's like playing a film. It looks killer. It succeeds in several visual milieu (black-and-white-shocked-with-pink film, CRT text adventure, PS1 early-polygonal surrealism). The atmosphere oozes style, but also mystery and menace. It's intellectual but satisfies the aesthetic senses. And the puzzles are pretty dang good.

I will add one caveat here, and it's a big one: I haven't finished this. I ran into an admittedly less-than-brilliant section asking you to traverse a big maze twice, paused my playthrough for a bit, and then real life intervened. If my opinion changes upon finishing it, I will update this post. But: this is a tale for adults, and I mean that not in the trite "video games aren't just for kids anymore" manner but in regard to the sophistication of its visuals and delivery, the respect for its audience, and the subject matter under examination. The sixteen hours I've played have been sleek, slick, and smart as hell.

MY GAME OF THE YEAR (REFUGE): As far game concepts go, "Animal Crossing with Sanrio characters" is one of the more natural fits. Now, granted: the mechanics in Hello Kitty Island Adventure are extremely gentle and forgiving (from forum posts, the game's a popular choice for parents to play with their children). You're here largely to explore and spend time in a pleasant place in the company of charming characters. But the game's very good - deceptively good - at encouraging that. The visuals are cute, bright, and happy, like a well-designed playset, with shapes and colors appealingly-chosen - it looks great in a way that's easy to overlook. The writing is funny and self-aware (possible response to quest prompt: "Unsurprisingly, it's up to me to fix the situation") but not snarky or too smart for its own good - it never forgets to center the essential sweetness of the characters and world. And it really does nail the socialization and "second home" aspect. As my own world was falling apart, this became a refuge. Hello Kitty knows. Hello Kitty understands.

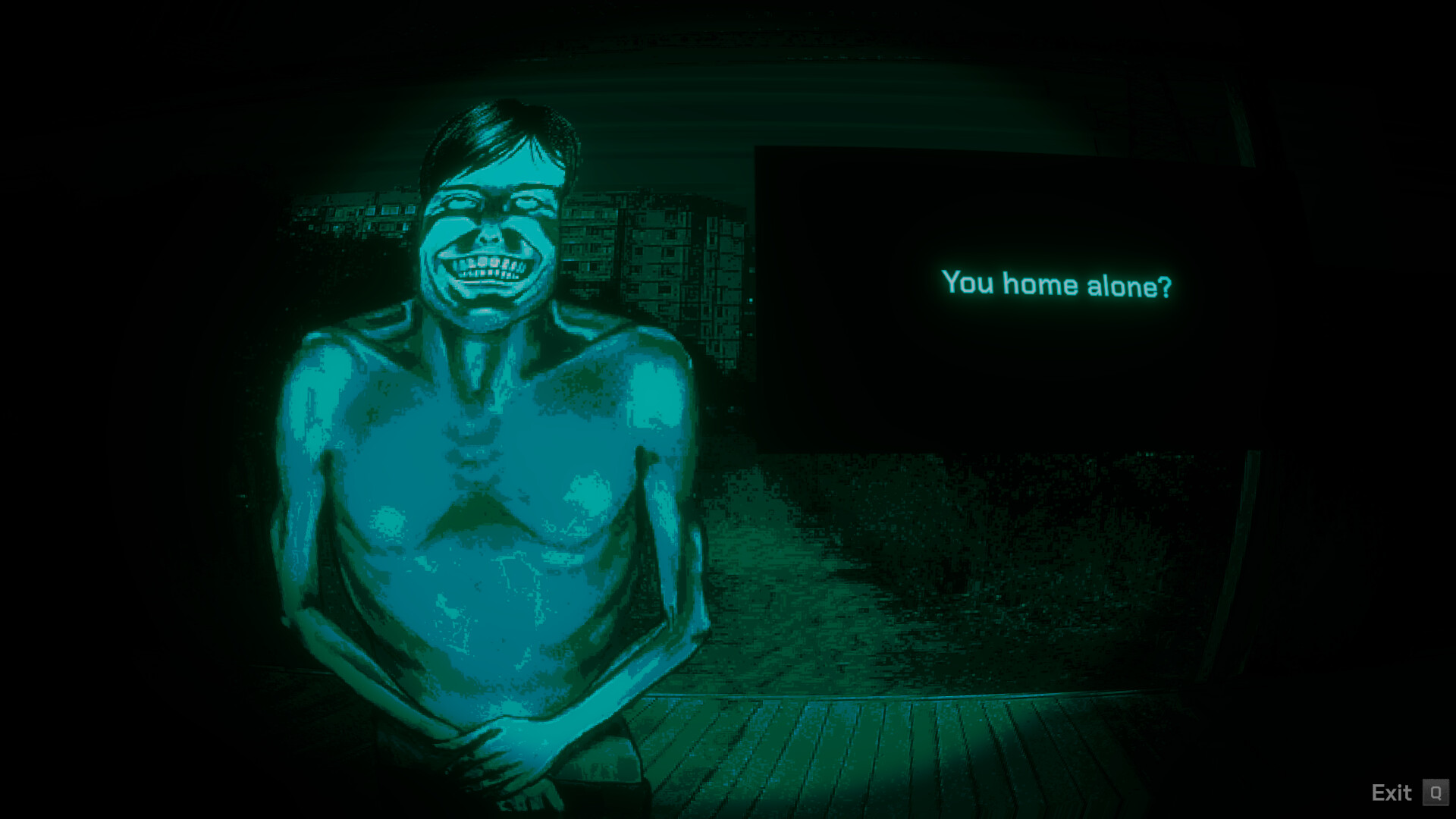

MY GAME OF THE YEAR (THEMATIC): No, I'm Not a Human is the vibe of the year and the game of our times. Solar flare activity is incinerating the unprotected populace during the day, and malevolent entities masquerade as friends and neighbors. The government is powerless at best and a band of marauding thugs at worst. At night, a barrage of strangers knocks at your door of your isolated farmhouse for refuge. How to tell friend from foe? You have some second-hand information, but nothing reliable beyond your gut, which will inevitably lead to imperfect choices. Your own past isn't safe, either. Even if you somehow muddle through, is it even worth surviving in this world? No, I'm Not a Human is bleak as fuck but somehow comforting, working the now-familiar vibe of monitoring the progress of the apocalypse from your home, elevated by the bizarre, ever-threatening surveillance monitor-green aesthetic and the slice-of-life personal stories from fellow survivors, or predators, among the ruins.

More thoughts on the year below!

In a year where I was deluged with real-life problems, I found myself turning to games to relax rather than experience the heights of the medium. This was originally going to be a section in my end-of-year post, but it got so long it's kind of unbalancing, so I'm making it a separate post.

Dragonsweeper is Minesweeper with experience, leveling, and a medieval aesthetic (guess what you're doing from the title). Use the numbers in the grid not to detect mines, but monsters - the numbers surrounding an unclicked square add up to the creature's HP. Hunt lesser medusae and mindflayers and try to tackle the grid's beasties in order of power to strengthen yourself for the titular confrontation. A neat, controlled experience, even with satisfying end screens.

I picked up Tower Wizard after it got some kind notices upon its release near a Steam sale. It's a basic clicker with mild resource management. The twee bichromatic pixel art is cute, and it has a mild sense of humor in the handful of times a sort-of plotline surfaces, but it's not worth seven hours of your time, nor any more space here.

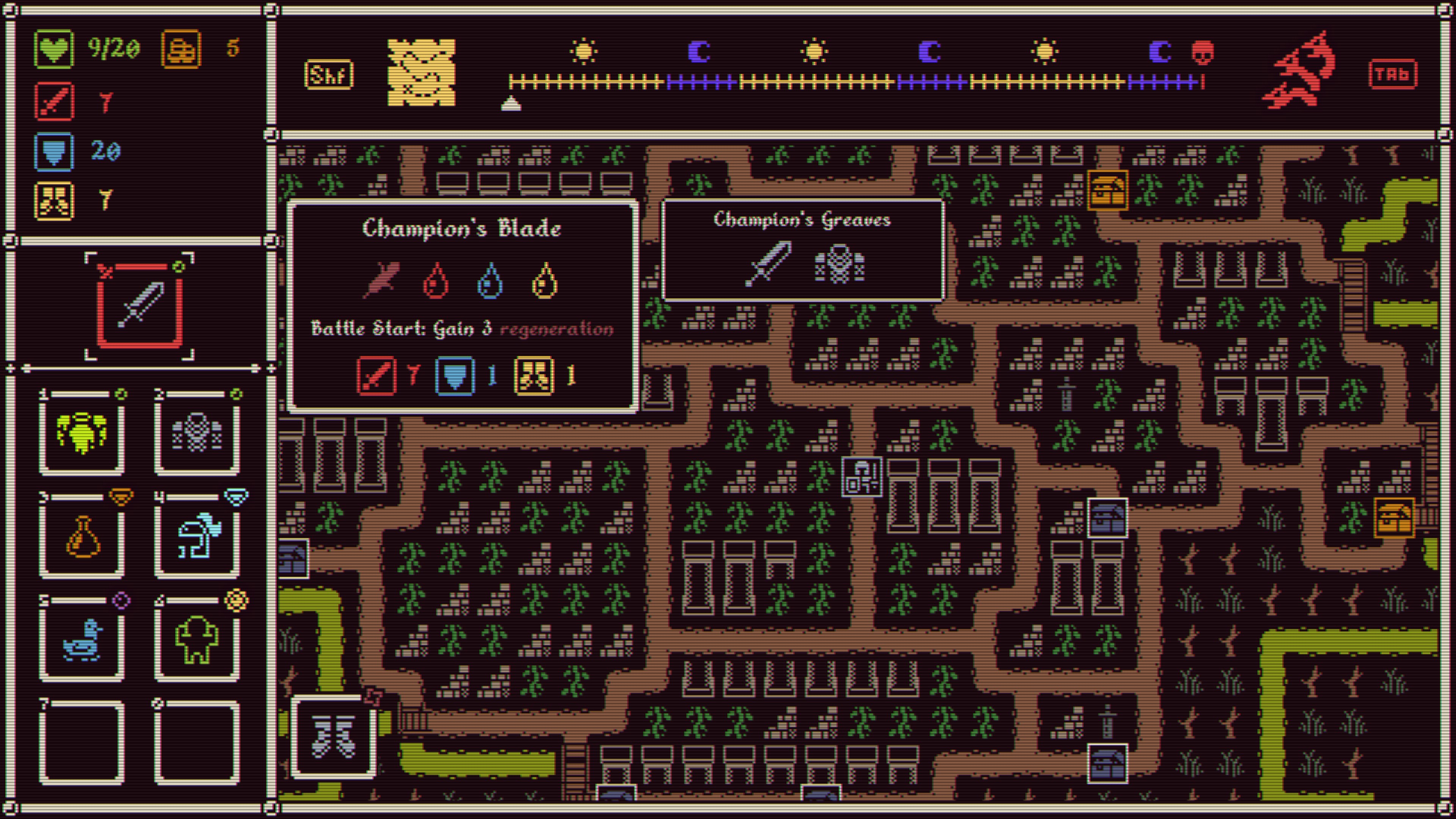

Don't worry; I didn't buy He Is Coming for the name. I bought it for the ad. In my defense, it's a good one, and its sense of style and humor carries over in the game's presentation, full of crunchy, old-style '80s CRPG visual & aural goodness crossed with bold colors and shapes. It's got a welcome, friendly brassiness in its assets I appreciate.

The gameplay isn't quite there yet: you've got a set number of steps to cover the land and scrounge up suitably-powerful equipment before HE comes, with combat handled via Loop Hero autobattles. (Like in Loop Hero, there are a number of loadout approaches you can take, which expand map by map.) Success yields subsequent rounds of stat escalation with a succession of HEs before the headliner HE deigns to descend. The game needs more bite and more to do during levels, though, as you'll see all the equipment and make your necessary choices fairly quickly. It's getting there. It's not *quite* there yet. I wouldn't recommended it at this stage, but I am rooting for it.

Save Room turns the RE4 attache case into a full-fledged game. You know from that description whether you want to fool with it. There's DLC (The Merchant) that's effectively a sequel, which features more levels and adds a parody story (the president's dog has been kidnapped; the Hunnigan analog is moonlighting as the merchant to get some extra cash out of the situation), but the plot runs out of steam halfway, the game's new mechanics get finicky, and the experience wears out its welcome early. The original delivers everything you want from the premise and is a fun, breezy coupla hours.

Glass Masquerade 4: Constellations is basically a jigsaw-puzzle game where the pieces are fragments of a stained glass window. My two complaints have remained the same since the first installment: a) the pieces often don't quite look like they fit in their proper spaces, particularly in the fiddly bits, and b) the menu you use to cycle through the pieces, presented as a pair of arcs on either side of the frame for the glass that are seemingly part of one circular tray, are actually not connected - they're two separate pools of pieces, which can lead you to miss stuff and proves continually aggravating throughout the game. Still, the stained glass windows are damn spectacular - not as celestial-themed as advertised, but still cool (if a little on the side of van art).

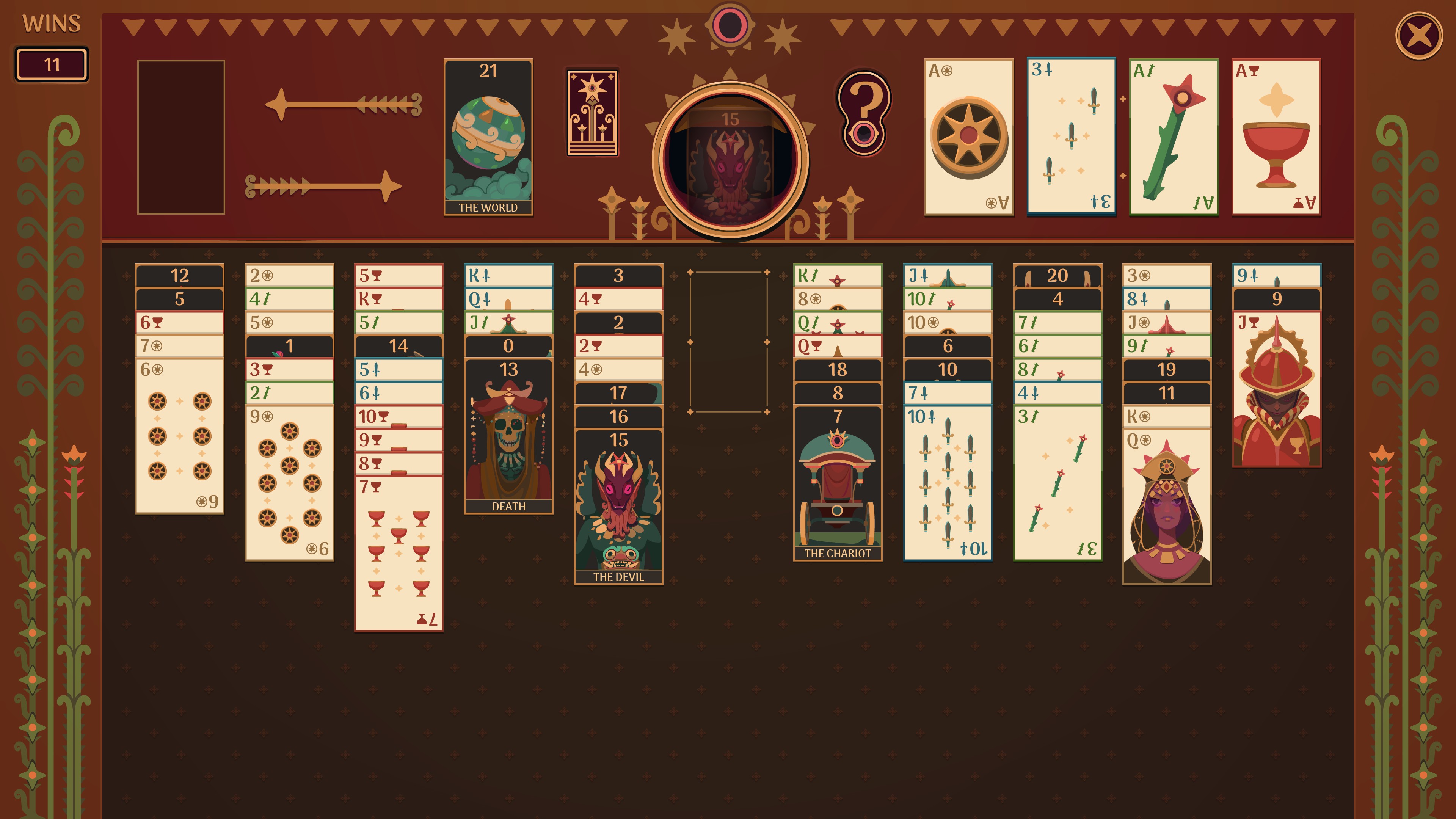

I grabbed the Zachtronics Solitaire Collection so I could have an easily-accessible version of their excellent Sawayama Solitaire (Klondike with a greater emphasis on skill), but I eventually found their advanced tarot-themed original solitaire game Fortune's Foundation almost as arresting. At first, it seems impenetrable, resistant to all progress. It wasn't until a comment on the forums from an unfortunately self-satisfied but aggravatingly-correct poster clued me into the key to victory: "What you want to do is consider each possible sequence of moves until you find one that terminates in an improvement in your situation." You have to think through every move to its absolute terminus and choose only those that leave you better-positioned, as the game is extraordinarily susceptible, by design, to being scuttled by one careless move. The ask on thinking ahead usually isn't too massive, though - and it's satisfying when your cautious planning is rewarded. Add a deck that's very handsome in palette and character design, and you have a winner, albeit one very reluctant to reveal itself as such.

I haven't played Unpacking, but I feel confident in saying that Whisper of the House is Unpacking if nothing made sense. Why do I have to put the big-screen TV either against a window, right in the glare of a window, or against the kitchen sink? Why am I forced to put the towel holder in the shower? Why can't I put eggs and milk in the refrigerator? Why do I have to put staple baking ingredients on shelves well above the user's head? Top it off with a translation that just isn't where it needs to be, and despite some cute pixel graphics, I just didn't feel like continuing with this title.

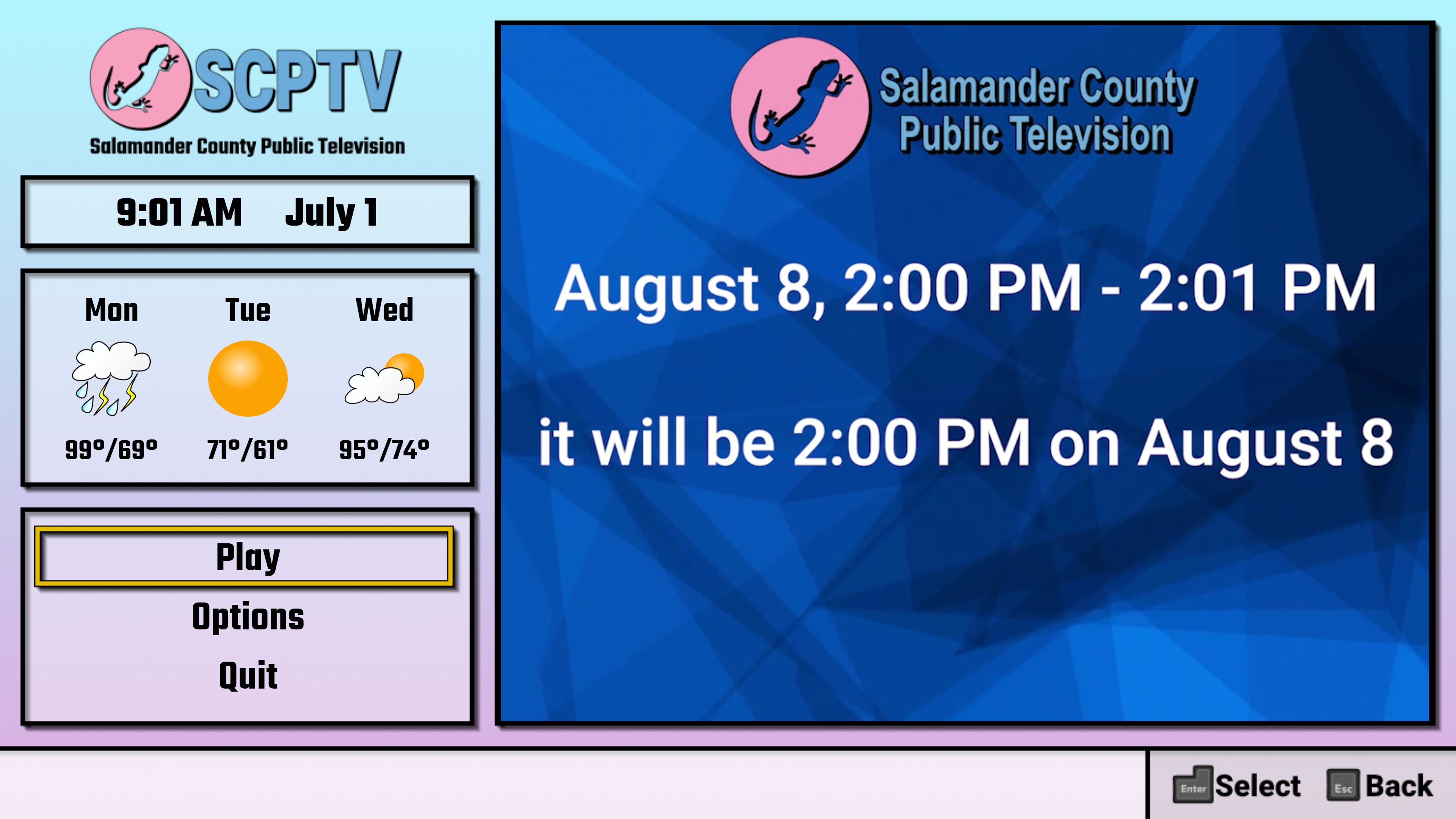

Salamander County Public Television is one of those games, like Pony Island, that's more a long-form joke than a game per se. You're producing content on local inanities while trying to figure out, on an extremely limited budget, why everyone in your viewing area has disappeared. Your attempts at broadcast material take the form of an absurdist minigame collection, but the focus is on the story unfolding via IMs in your office Slack, all interspersed with FMV content from the station.

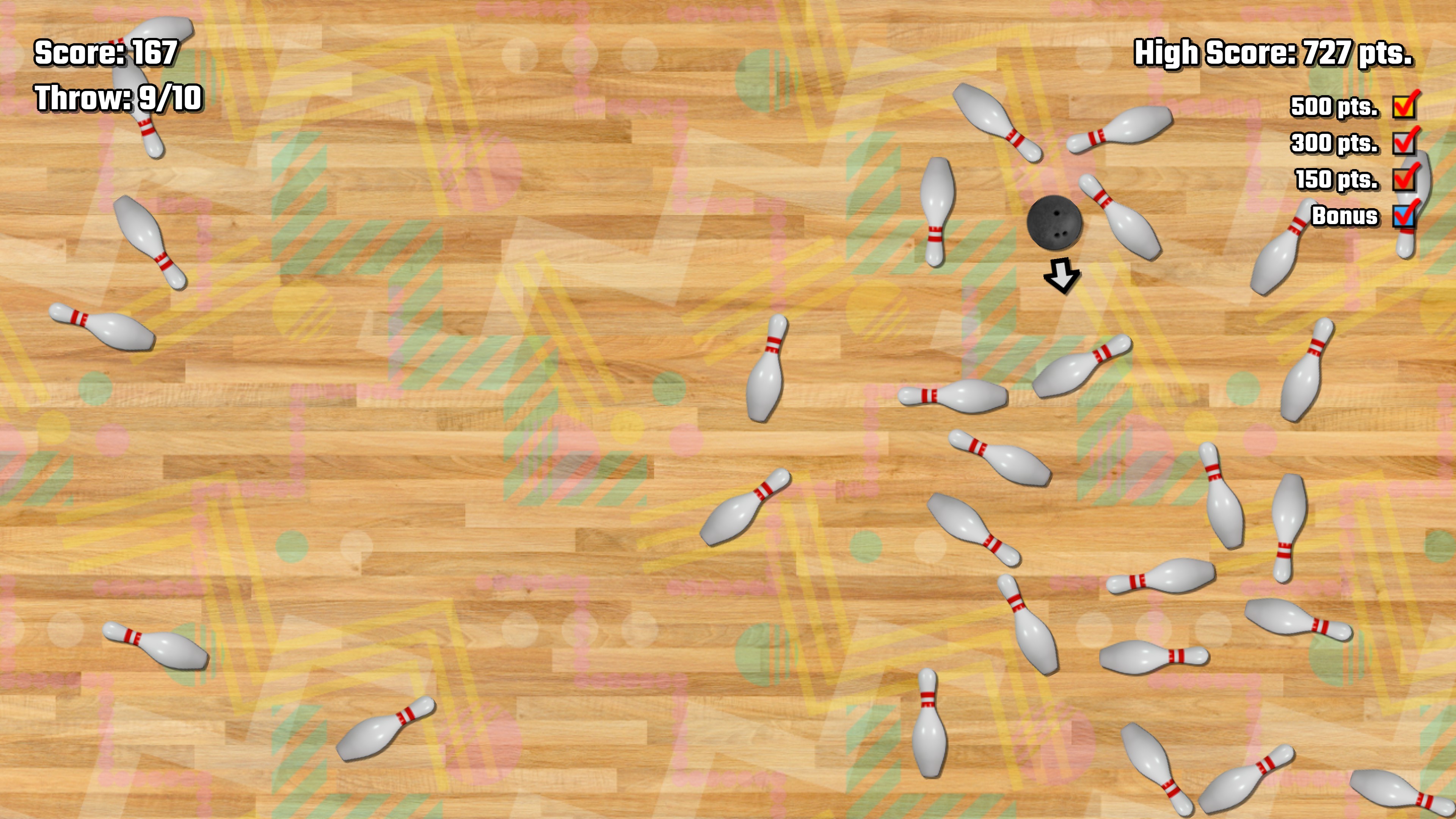

Props for Mitosis Bowling, though, a pool-like minigame where every pin the ball hits splits into two, and soon you're just knocking about a satisfyingly absurd number of pins. They should've leaned harder into the cacophony aspect that lights up the "toddler with busy box" center of your brain and made the ball go fast more reliably for maximum knockabout, but good job on this one still.

I came away from Kid Icarus: Myths and Monsters feeling it was kind of limp. It includes a few negligible innovations (you can flap Pit's wings to slow his descent during falls; you can now use hammers to hit walls and uncover bonus rooms), but the game is mostly a weaker retread of the NES original with a bataa-kusai sheen (dorky music; Palutena's Princess Di '80s do). The structural duplication is slavish, right down to thief enemies populating a horizontal second-stage overworld. It does require strength upgrades more urgently, so be sure to park yourself in front of a snake pot and hit 100 of those suckers every level to keep on pace; in exchange, the killer vertical platforming is nerfed - the screen just scrolls back down - but that seems to detract from the game's bite and character somehow. They also make the last level shoot-'em-up work like a Mario 1 underwater level - you gotta pump A constantly to stay afloat, which is a big, miscalculated distraction when you're also trying to pump the final boss full of arrows. No vaporwave in black-and-green, either. Even Castlevania Legends, a game some consider soulless going-through-the-motions that biffs some of the franchise basics, had original ideas and mojo; while OMaM has a few halting half-steps in the direction of improvement, I found more spark in this page of Of Myths and Monsters' manual than I did in the entire game.

Shock Troopers was meant to be a twin-stick shooter. It is not a twin-stick shooter. The game instead just locks you into facing whatever direction in which you're proceeding after a second, which fatally hobbles your ability to react to threats. The game features a huge, appealing cast of possible protagonists and sparkles with Neo Geo pixel art charm but was ultimately, for me, near-unplayable due to the inadequate controls. Yes, I know I'm a minority opinion on this front. I'm the problem.

Back when my Flight Rising account was still active, I played a lot of a Flash-style Bust-a-Move clone that earned you in-game currency. I decided to give the name brand a whirl after seeing it on sebmal's randomizer stream, through both the arcade two-pack on Steam and a rom of the SNES title. Unfortunately, all proved inferior to the generic due to a decidedly nasty streak: the games are programmed to give you frequently the worst color bubble for your current position or a setup that puts you right back in the difficult position where you started (four bubbles of the same otherwise-rare color, for instance). This is consistent between versions, and unwelcome. Having played a knock-off of the game where success relies on skillful planning and aiming, not cheap tricks, made this encounter all the more unfortunate. (Also aggravating: the arcade versions feature a Bub and Bob who are always, always keening & sobbing over your allegedly-dismal progress, no matter how you're actually doing, as well as some of the absolute most annoying voice samples known to man.)

Finally, I'll stick to my HowLongtoBeat assessment of the maze-chase puzzler Hello Kitty's Magical Museum:

If you like the spates on this blog where I talk on and on about Lunar, you might enjoy the responses I and others have written to the thoughtful questions the Tumblr fyeahlunar posed for this year's Lunar Week celebration. (For posterity, here's everything I've blogged and reblogged about Lunar on that platform. 34 pages as of this writing!)

Page 1 of 56